NEP 2020 in the Northeast

Challenges and Pathways to Inclusive Implementation

Published Date: November 8, 2025, Updated Date: November 8, 2025

Abstract

The New Education Policy (NEP) 2020 is sought to have a comprehensive reform agenda for Indian schooling and higher education, yet its implication into state-level practice has been quite uneven, especially in the Northeastern States of India. This paper investigates on why several Northeastern states have been slow or yet to adopt the NEP, and what kind of problems they are facing. The paper draws multiple state-level case studies and examines how context-sensitive and community-led models of implementation have addressed linguistic and infrastructural barriers on other parts in India. The findings indicate that the key problems in the Northeastern region, in the form of structural and administrative constraints that continue to slow effective policy implementation. The paper concludes with actionable, evidence-informed recommendations that might help to support equitable and culturally grounded NEP implementation across the Northeastern states.

Keywords: New Education Policy, Northeast India, Multilingual Education, Educational Implementation, Cultural Inclusion

Introduction

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 is widely described as a far-reaching reform that reorients India’s school and higher-education architecture toward greater flexibility, multilingualism and contextual learning. As of now, the policy is advisory in nature and its success therefore depends on state-level adoption and adaptation rather than a single centralised rollout [1]. Several states have moved quickly to translate the NEP into state programmes and orders soon after 2020, signalling that political will and administrative readiness can produce some rapid changes. But at the same time, other states have delayed or have phased or selectively adopted NEP provisions, and a number of states have publicly expressed reservations or slowed formal adoption for political, administrative and resource reasons.

Within the Northeastern region the several reporting has showed an uneven uptake: Assam has formally signalled a shift from the 10+2 structure to the NEP’s 5+3+3+4 architecture and has taken some concrete steps in teacher-education alignment, whereas several other Northeastern states have not reported full state-level implementation or have proceeded more cautiously [2]. The policy-analysis literature identifies several structural and operational constraints that help explain such caution. Geographic remoteness, weak physical connectivity and persistent gaps in school digital readiness limit the feasibility of several NEP initiatives that assume reliable infrastructure and online resources [3]. At the same time, acute multilingualism and the presence of many local dialects make mother-tongue instruction logistically complex without substantial investment in locally-relevant curricular materials and teacher preparation; teacher shortages and uneven teacher training capacity further complicates the capacity to operationalise NEP’s educational shifts [4].

Taken together, recent studies and policy reports converge on two central points that frame the research gap addressed in this paper: first, the NEP’s advisory, state-centred design produces inevitable variation in pace and form of implementation across India; and second, Northeastern states face distinctive structural, linguistic and capacity constraints that make direct transposition of the national framework difficult without targeted adaptation, funding and intergovernmental cooperation. This paper therefore establishes the provisional claim that the uneven implementation in the Northeast is less a question of principle and more a set of practical barriers that require context-sensitive solutions.

Objective

The study examines the implementation of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 in the Northeastern region, focusing on key obstacles such as poor digital and physical infrastructure, shortage of trained teachers for multilingual instruction, and persistent socio-economic barriers like poverty and child labour that weaken school retention. The objective is to identify practical, inclusive, and region-specific measures to ensure effective and equitable NEP implementation across the Northeastern states.

Challenges

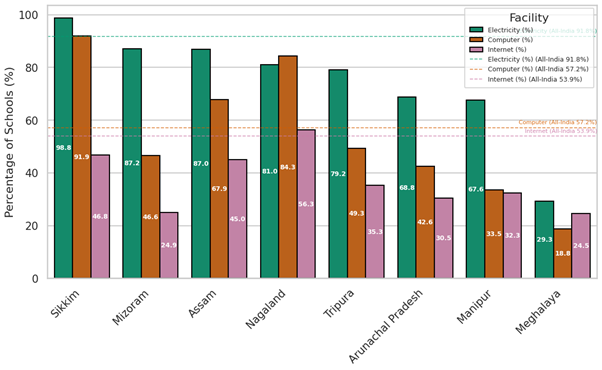

Physical and digital infrastructure is one of the Northeast’s problems as it remains uneven throughout the region which reduces the reforms that the NEP wants to bring in to. Rugged terrain, dispersed settlement patterns, and weak road, electricity and network connectivity raise the cost of providing reliable school facilities. Internet penetration is also very less and many schools lack digital resources (like digital boards, computer labs, projectors etc). Empirical studies and state-level reviews of the NEP rollout emphasise that the digital divide and basic infrastructural shortfalls will directly translate into unequal access to the benefits of the reforms across districts and communities [5].

Figure 1: State-wise Percentage of schools by facilities in Northeastern States

Source: Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE+) 2023–24; analysis based on data compiled in “Digital Infrastructure in Schools: Challenges and Progress in India,” Education for All in India (2024).

Linguistic diversity, even though is seen as an academic strength, poses significant challenges for implementing the NEP’s reforms. In several Northeastern states, students in classrooms often speak multiple local languages or dialects in addition to Assamese, Hindi, or English, and many tribal languages still lack standardized textbooks, reading materials, and formal teacher-training programs. As a result, the efforts to introduce home-language instruction encounters major logistical barriers, such as shortages of locally relevant curricula, the absence of standardized writing systems for some languages, and limited teacher preparation in multilingual or bilingual pedagogies etc [6].

Table 1: State-wise Report of Languages and Population of Speakers in Northeast India

| Sl. No. | States | Official Languages** | Medium of Instruction Till class 5** | Report of Languages* | Other languages and dialects* | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Languages | Population of Speakers | Languages/ Dialects | Speakers’ Population | |||||||||||||||

| 1. | Arunachal Pradesh | English | English | Nissi, | Adi, Bengali, Others | 3,95,745; 2,40,026; 1,00,579; 6,47,377 | Mishmi, Monpa, Nocte, Tangsa, Wancho | 42,017, 12,398, 30,308, 36,546, 58,450 | ||||||||||

| 2. | Assam | Assamese, Bengali, | Bodo, | English | Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, English | Assamese, Bengali, Hindi, Others | 1,50,95,797; 90,24,324; 21,01,435; 49,84,020 | Bodo, Bishnupriya, Deori, Dimasa, Karbi, Lalung, Mishing, Rabha, | 14,16,125; 53,867; 27,441; 1,31,474; 5,11,732; 38,281; 6,19,197; 1,01,752 | |||||||||

| 3. | Manipur | Manipuri | Hmar, Lushai, Manipuri, | Paite Tankhul, Thadou | Manipuri, | Mao, Thado, Others | 15,22,132; 2,24,361; 2,33,779; 8,85,522 | Tangkhul Anal, Gangte, Hmar, Kabui, | Kom, | Kuki, | Lakher, | Liangmai, Maram, Maring, Paite, | Vaiphei | 1,83,091; | 26,508; 15,274; 49,081; 1,09,616; | 14,621; 30,875; | 41,876; 45,546; 32,098; 25,657; 55,031 | |

| 4. | Meghalaya | English, | Garo, | Khasi, | Pnar | English, | Garo, | Khasi | Bengali, Garo, | Khasi, | Others | 2,32,525; 9,36,496; 13,82,278; 4,15,590 | Karbi, | Rabha | 14,380; 21,671 | |||

| 5. | Mizoram | English, | Mizo | English | Bengali, Mizo, Lakher, Others | 1,07,840; 8,02,762; 42,876; 1,44,727 | ||||||||||||

| 6. | Nagaland | English | English | Konyak, | Ao, | Lotha, | Others | 2,44,135; 2,31,084; 1,77,488; 13,25,795 | Angami, Chakesang, Chakri/Chokri, | Chang, Khezha, Khiemnungan, | Phom, Pochury, Rengma, Sangtam, Sema, Yimchungre, Zeliang | 1,51,883; 17,919; 91,010; | 65,632; 34,218; 61,909; | 53,674; 21,446; 61,537; 75,841; 8,268; 74,156; 60,399 | ||||

| 7. | Tripura | Bengali, English | English, Bengali | Bengali, Tripuri/ Kokborok, Hindi, Others | 24,14,774; 9,50,875; | 77,701; 2,30,567 | Bishnupriya, Halam, Mogh | 22,112; 23,089; 35,722 | ||||||||||

| 8. | Sikkim | English | English | Nepali, Hindi, Bhotia, Others | 3,82,200; 48,586; 41,889; 1,37,902 | Lepcha. Limbu, | Rai, | Sherpa, Tamang | 38,313; 38,733; 7,471; 13,681; 11,734 |

Source: Language & Language Teaching, Issue 24 — “Contextualising Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education.” LLT Foundation, 2023. Available at

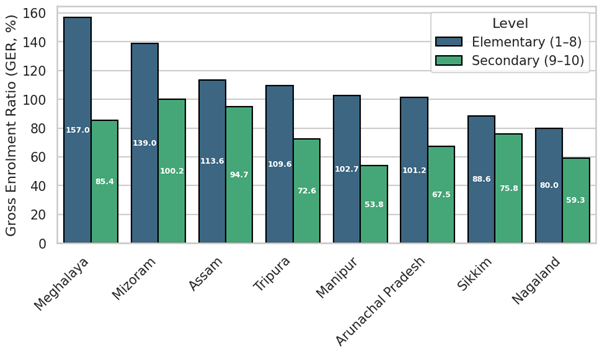

Poverty, socio-economic factors and livelihood patterns also play a role in reducing school retention and learning outcomes among several tribal communities. Studies showed a higher dropout rates and lower enrolment of students at secondary level in many of the tribal districts. Factors such as seasonal labour, early marriage, and the often neglected economic costs of schooling also lead to non-attendance. The school curriculum is also sought to be as culturally disconnected from local life, as it rarely or not at all, includes indigenous knowledge, livelihood practices and local histories, resulting in many families and children putting less and less importance on formal education [7].

Figure 2: Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) of Tribal Students in Northeastern States

Source: Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE+) 2021–22, Ministry of Education, Govt. of India; compiled from Newslaundry (2025).

All the evidences, stated above suggests that implementing NEP in the Northeastern states is less of a question that the policy aims for than redesigning the functional pathways through which those aims can be turned into reality; for which interventions must be done on incremental basis, resourced and locally adapted with proper attention to infrastructure, multilingual curriculum development, training of teachers suited for linguistic pluralism and financing methods that prioritise historically unprivileged communities. Recent field studies therefore point to a single strategic vital contextualization, coupling with capacity building, only if NEP promises to be inclusive, culturally grounded learning could be done in the Northeast [8].

Case Studies

Assam: Mising Medium Schools Initiative

In Assam, there were only 4 languages (English, Assamese, Bodo, Bengali) that used to be taught until Class 5, for which many languages of the tribal communities like the Mising were left out from the formal education system of Assam. So, to align with the National Education Policy (NEP) emphasis on indigenous languages, Assam government introduced Mising Medium schools’ initiative.

At the beginning of the 2025–26 academic year, Assam designated 200 lower primary schools to introduce Mising as the medium of instruction for Grades 1 to 5, to adopt a three-language model of Mising, Assamese, and English with community participation in textbook preparation. This move is part of a broader state effort to formally recognise several tribal languages as mediums of instruction in early education and to align with the National Curriculum emphasis on mother-tongue instruction at foundational stages.

According to academicians, the introduction of Mising as a medium in the primary classes will significantly increase the understanding of the kids about the contents of their curriculum. However, while the programme’s initial rollout to 200 schools has created a platform for monitoring outcomes such as attendance and early-grade learning, robust assessment of large-scale impact will require standardized baseline and endline measures to quantify learning gains and retention. [9] [10].

Arunachal Pradesh: Nyubu Nyvgam Yerko & digital classrooms

Arunachal Pradesh is one of those states where implementation of NEP policies would face the highest problems due to the lack of proper digital infrastructure, proper books and resources to preserve their traditions and heritage etc.

In alignment with the National Education Policy (NEP) emphasis on indigenous knowledge and mother-tongue instruction, Arunachal Pradesh has launched initiatives to institutionalize native-language education and integrate technology in classrooms. A key example is the Nyubu Nyvgam Yerko School in East Kameng district, established by the Donyi Polo Cultural & Charitable Trust to promote local traditions, oral heritage, and indigenous languages through formal education [11]. Complementing this, the state has also introduced digital classroom initiatives under the “Digi Kaksha” programme to provide multimedia teaching resources to remote schools and enhance access to quality learning materials [12] [13]. These dual initiatives aim to preserve and transmit indigenous knowledge while leveraging technology for educational inclusion, aligning with NEP goals of multilingualism, cultural grounding, and technology-enabled active learning.

Initial reports and community feedback indicate that the Nyubu Nyvgam Yerko School has been well-received for its role in revitalizing indigenous languages and fostering cultural preservation through curriculum design that reflects local traditions and values [11]. Meanwhile, the Digi Kaksha smart-classroom initiative has enriched the teaching process with interactive multimedia content, improving student engagement and access to digital learning tools, even in remote areas [12]. However, challenges remain regarding connectivity, teacher training, and infrastructure gaps, which limit the scalability of these programmes in several hill districts. These barriers mirror broader national challenges in implementing NEP recommendations concerning technology integration and capacity building across geographically diverse regions.

Manipur: Meetei Mayek revival, tribal-language materials and higher-education alignment

Meetei community of Manipur has long been using the Bengali script to write their language, for which they faced certain problems like absence of certain sounds etc. Along with this, there are several other tribal communities residing in Manipur along with the Meetei community that lack resources, materials and dictionaries, that are needed to preserve their local languages.

For which the state has invested in promoting the Meetei Mayek script and producing teacher-training materials and dictionaries for Manipuri and several tribal tongues, while higher-education institutions such as Manipur University have begun aligning to the National Education Policy 2020-style flexible degree structures and online/vocational components. For example, Meetei Mayek training and coaching books have been provided in coaching and refuge relief camps [14]. The state aims to strengthen script and language resources for classroom use, preserve cultural identity via curricular inclusion, and to operationalise NEP priorities in higher education like flexible degrees, apprenticeships and online learning to increase employability and local relevance (See syllabus reform at Manipur University [15]).

Community-level training events and resource compilations for Meetei Mayek and tribal phonologies have raised awareness and teacher capacity in the short term. Higher-education reports show institutions experimenting with NEP-aligned degree structures. For instance, Manipur University’s announcement: Implementation of NEP 2020 way forward with reference to Employability, Vocational Studies & Skill Development [16]. However, long-term success depends on developing graded instructional materials, continuous mentoring for teachers, and institutional changes to assessment and credit frameworks.

Meghalaya: STEM infusion, Khasi and Garo in early grades

Khasi and Garo are one of the major communities of Meghalaya, yet they lack STEM education like Artificial Intelligence (AI) and other emerging-technologies that are crucial skills to learn in the 21st century. In addition to that, their current education system lacked proper implementation of Khasi and Garo languages until the primary level (i.e. until class 4).

So, to tackle this, the state government has announced its plans to introduce Robotics, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and other emerging-technologies into the school curriculum, while expanding early-grade instruction in indigenous languages Khasi and Garo as part of a reform aligned with the National Education Policy 2020 (NEP). The aim is to combine 21st-century skill development (through STEM/technology) with cultural and linguistic preservation (through mother-tongue learning) [17] [18].

Initial evidence shows that the policy is indeed in motion: digital-reports indicate that robotics/AI and IoT are being integrated and STEM labs planned across schools; likewise, a draft discussion paper proposes making Khasi and Garo compulsory up to Class 4, with bilingual textbooks in the pipeline. However, the rollout faces concerns such as teacher training, resource allocation, infrastructure (labs, connectivity) and equitable distribution across districts. For instance, the Education Department’s discussion paper highlights a shortage of trained Khasi and Garo teachers as a challenge [19].

Nagaland: Tribal-language curricula, teacher certification and cultural integration

Nagaland is one of the most diverse states in the Northeast, which comes with its own set of problems. Many of its tribes’ languages are oral and lack a proper script and grammar. In addition to this, their education system lacked resources related to their culture and heritage.

So, in order to fix this, the state is advancing its education reform agenda by strengthening mother-tongue instruction and cultural integration in schools. Through collaboration between Nagaland University and the state’s education department, the government is undertaking curriculum development and teacher certification initiatives in tribal languages, and formalising arts and music education in elementary grades by aligning with the National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) goals of contextualised, inclusive education [20] [21] [22].

Public statements and education briefs show that foundational steps have been taken: Nagaland University is launching an MA programme in Language and Culture designed to boost indigenous-language scholarship, teacher capacity and curriculum resources [23] [24]. Under its tribal language grammar-development initiative, NU and the state education department are working on pedagogical grammars for 18 recognised languages for Classes 5-12, signalling serious curricular commitment” [21] [25]. Yet the real challenge remains at classroom level that is scaling quality materials, certifying and mentoring teachers in tribal languages, and adapting assessment frameworks to recognise cultural and linguistic content will be essential if policy announcements are to translate into consistent change across schools.

Tripura — Kokborok expansion and tribal-language inclusion through Class XII

Tripura, the state named after twipra tribe, who were the original inhabitants of the region faced certain problems like their language Kokborok wasn’t a mainstream language in their region and instead the tribals had to rely on learning Bengali for their education.

For which the state has actively mainstreamed Kokborok and other tribal languages by expanding Kokborok-medium instruction across primary and secondary schools and allowing students to sit for state exams and professional qualifications in Kokborok. The state’s aim is to ensure tribal-language students have continuous access to education and examinations in their native language up to Class XII and beyond, thereby reducing barriers to higher education and public-service entry while preserving cultural and linguistic heritage [26].

Reports show measurable policy steps: for example, Kokborok is taught as a subject in over 1,100 schools from Classes I–V, 133 from VI–VIII, 115 at IX–X and 65 at XI–XII in the state. The department has published textbooks for Classes IX–XII, launched teacher-training programmes, and prepared for broader adoption in examinations [27]. Nonetheless, full realisation depends on rigorous textbook development, examiner/teacher training, and systemic acceptance of tribal languages in formal assessment and higher-education pathways.

Discussions

From the above case studies of Assam and Tripura we can say that the linguistic adoption for several tribal languages is an ongoing process and each state is making their own move in implementing mother language inclusion for several of their tribal languages, through it is slow and to see its full impact, it would take a couple more years. As of now, it is showing positive changes and several tribes, in future, will be able to learn in their native languages. The government must ensure that proper policy measures are taken to preserve the tribes’ native language thereby including as much of the tribal languages into the school and higher educations’ curriculum as much as possible. The government must also ensure the availability of proper physical and digital infrastructure in order to fully implement the NEP’s policies along with empowering the tribals by introducing schemes to ensure, children are able to continue their education without much hassle and also to reducing dropout rates among them. Such implementation can be properly seen in the case studies of Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya where the government in Arunachal Pradesh has implemented digital classroom in the Nyubu Nyvgam Yerko School in East Kameng district. And in the case of Meghalaya, the implementation of STEM education has been introduced in the Khasi and Garo languages to make children learn STEM education in their native languages. The case studies of Manipur and Nagaland show the steps the government is taking in order to preserve their native scripts and languages. In case of Nagaland, many of their local languages are just spoken orally so the government has taken initiative to formalise the script and grammar of 18 of their tribal languages, which is a crucial step to implement native language education for the locals and also for NEP.

Conclusion

As of now, the Northeastern states’ priority is to ensure that all of their local languages are preserved, formalised, have a proper written form and is at least taught until the primary level in the regions where those languages are spoken in order to effectively NEP policies. After that, the states should focus on reducing other hurdles, faced by the students like infrastructural barriers, digital connectivity, poverty and socio-economic difficulties etc. in order to make sure the NEP policies, when implemented, are even throughout the region, and no community or region is left behind. Along with that, the states should also conduct proper training and capacity building programmes to equip educators with necessary skills required for multilingual, digital and holistic teaching. At last, a stronger collaboration between the central and the state government, along with active community participation will be required in order to ensure NEP’s success in the Northeastern region.

References

- Desk I. & Jadeja B. (2025, April 18). National Education Policy (NEP) 2020: Reshaping Indian Education for the 21st Century - IMPRI Impact and. IMPRI Impact and Policy Research Institute. https://www.impriindia.com/insights/nep-indian-education/

- Nath H. K. (2021, November 24). Assam Government to implement new education structure under NEP. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/news/story/assam-government-to-implement-new-education-structure-under-nep-1880445-2021-11-24

- Barman V. (2023, March). The state of access, digital connectivity, and inclusion in North Eastern Region of India: An issue brief (Issue Brief). Council for Social and Digital Development; Digital Empowerment Foundation. https://www.defindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/The-State-of-Access-Digital-Connectivity-and-Inclusion-in-North-Eastern-Region-of-India-2023_PRINT-1.pdf

- The Times of India. (2025, June 22). Nagaland MP urges Rio to recognise tribal dialects as ‘third language.’ The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/nagaland-mp-urges-rio-to-recognise-tribal-dialects-as-third-language/articleshow/122009201.cms

- Education for All in India. (2025, August 7). Digital infrastructure in schools: Challenges and progress in India, An Analysis Based on UDISEPlus 2023-24 Data concerning the Availability of Electricity Connection, Computer & Internet Connectivity. Education for All in India. Education for All in India. https://educationforallinindia.com/digital-infrastructure-in-schools-challenges-and-progress-in-india/

- Dkhar H. & Kakoty P. (2023, November). Contextualising Mother Tongue-Based, Multilingual Education in the Landscape of North East India: Prospects and Challenges. Learning and Teaching and Technology Lab. https://llt.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Contextualising-Mother-Tongue-Based-issue-24.pdf

- Jadhav V. & IndiaSpend. (2025, July 7). Why are tribal students dropping out after primary school?. Newslaundry. https://www.newslaundry.com/2025/07/07/where-tribal-students-are-left-behind

- Maniar V. (2022, February 5). Resource constraints in implementing the NEP 2020. Economic and Political Weekly. https://www.epw.in/engage/article/resource-constraints-implementing-nep-2020

- Kalita K. (2025, February 19). Govt introduces Mising language as medium of instruction in schools. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/govt-introduces-mising-language-as-medium-of-instruction-in-schools/articleshow/118395861.cms

- Pegu B. (2025, April 3). Introducing mising medium in primary schools in Assam: Why is there a need for a Tribal language Act?. Mising Community Researchers’ Collective. https://mcrcindia.com/2025/04/03/introducing-mising-medium-in-primary-schools-in-assam-why-is-there-a-need-for-a-tribal-language-act-2/

- Donyi Polo Cultural & Charitable Trust. (n.d.). Nyubu Nyvgam Yerko – Rang Gurukul. Donyi Polo Cultural & Charitable Trust. https://www.dpcct.org/nyubu-nyvgam-yerko-rang

- Team My Gov. (2024, September 13). DIGI-KAKSHA revolutionizing education in Arunachal Pradesh. My Gov. https://blog.mygov.in/digi-kaksha-revolutionizing-education-in-arunachal-pradesh/

- Mehta, Y. (2023, May 29). Arunachal Pradesh gets state’s first smart government school ‘Digi-kaksha’ in remote Tirap district. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/news/story/arunachal-pradesh-gets-states-first-smart-government-school-digi-kaksha-in-remote-tirap-district-2385812-2023-05-29

- The Sangai Express. (2023, August 23). Meitei Mayek coaching camp begins. The Sangai Express. https://www.thesangaiexpress.com/Encyc/2023/8/26/IMPHAL-Aug-25Meetei-Erol-Eyek-Loinasillol-Apunba-Lup-MEELAL-and-Directorate-of-Language-Planning-Implem.html

- Manipur University. (n.d.). Syllabus for UG Programmes. Manipur University. https://www.manipuruniv.ac.in/p/ug-programmes-syllabus

- Manipur University. (n.d.). “Implementation of N.E.P - 2020: Way Forward” with reference to Employability, Vocational Studies and Skill Development. Manipur University. https://www.manipuruniv.ac.in/news/implementation-of-n-e-p-2020-way-forward-with-reference-to-employability-vocational-studies-and-skill-development

- Sentinel Digital Desk. (2025, February 1). Meghalaya to introduce robotics and AI in school curriculum. The Sentinel - of This Land, for Its People. https://www.sentinelassam.com/north-east-india-news/meghalaya-news/meghalaya-to-introduce-robotics-and-ai-in-school-curriculum

- The Shillong Times. (2025, April 11). Khasi & Garo may become compulsory up to Class IV level. The Shillong Times. https://theshillongtimes.com/2025/04/11/khasi-garo-may-become-compulsory-up-to-class-iv-level/

- Government of Meghalaya, Education Department. (2025, 9 April). Discussion Paper: Introduction of Compulsory Khasi & Garo Languages in Schools. Government of Meghalaya, Education Department. https://northeastlive.s3.amazonaws.com/media/uploads/2025/04/Language-Policy-Discussion-Paper.pdf

- Nagaland Post. (2025, August 5). NU introduces MA in Language and Culture. Nagaland Post. https://nagalandpost.com/nu-introduces-ma-in-language-and-culture/

- Express News Service. (2025, September 1). Nagaland: Developing written grammar for 18 recognised languages. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2025/Sep/01/nagaland-developing-written-grammar-for-18-recognised-languages-2

- Kalita K. (2025, September 1). Nagaland scripts a new chapter as NU plans written grammar for 18 dialects. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/nagaland-scripts-a-new-chapter-as-nu-plans-written-grammar-for-18-dialects/articleshow/123641083.cms

- Chhapia H. (2025, August 5). Nagaland University launches interdisciplinary master of arts in language and culture. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/nagaland-university-launches-interdisciplinary-master-of-arts-in-language-and-culture/articleshow/123112378.cms

- Mansi. (2025, August 5). Nagaland University launches MA in Language and Culture. India Today. https://bestcolleges.indiatoday.in/news-detail/nagaland-university-launches-ma-in-language-and-culture-4891

- Nagaland Post. (2025, September2). NU leads to develop grammar for 18 Naga languages. Nagaland Post. https://nagalandpost.com/nu-leads-to-develop-grammar-for-18-naga-languages/

- The Times of India. (2025, January 19). Tripura edu min bats for inclusion of Kokborok in Eighth Schedule of Constitution. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/tripura-edu-min-bats-for-inclusion-of-kokborok-in-eighth-schedule-of-constitution/articleshow/117378014.cms

- Chakraborty T. (2025, January 16). Kokborok language mapping project nears completion: Tripura CM Manik Saha. India Today NE. https://www.indiatodayne.in/tripura/story/kokborok-language-mapping-project-nears-completion-tripura-cm-manik-saha-1155404-2025-01-16

This is an excerpt from NEP 2020 in the Northeast article. I highly recommend you give it a read!